The Extravagant Intimacy of Pipilotti Rist

The New Museum seems to have taken it upon itself to produce spectacles that are as moving as they are eye-filling. Pipilotti Rist: Pixel Forest is something else again.

The first time I encountered a piece by Pipilotti Rist was the summer of 2006 at the exhibition Into Me/Out of Me, curated by Klaus Biesenbach at PS 1, which included a 43-second video loop called “Mutaflor” (1996).

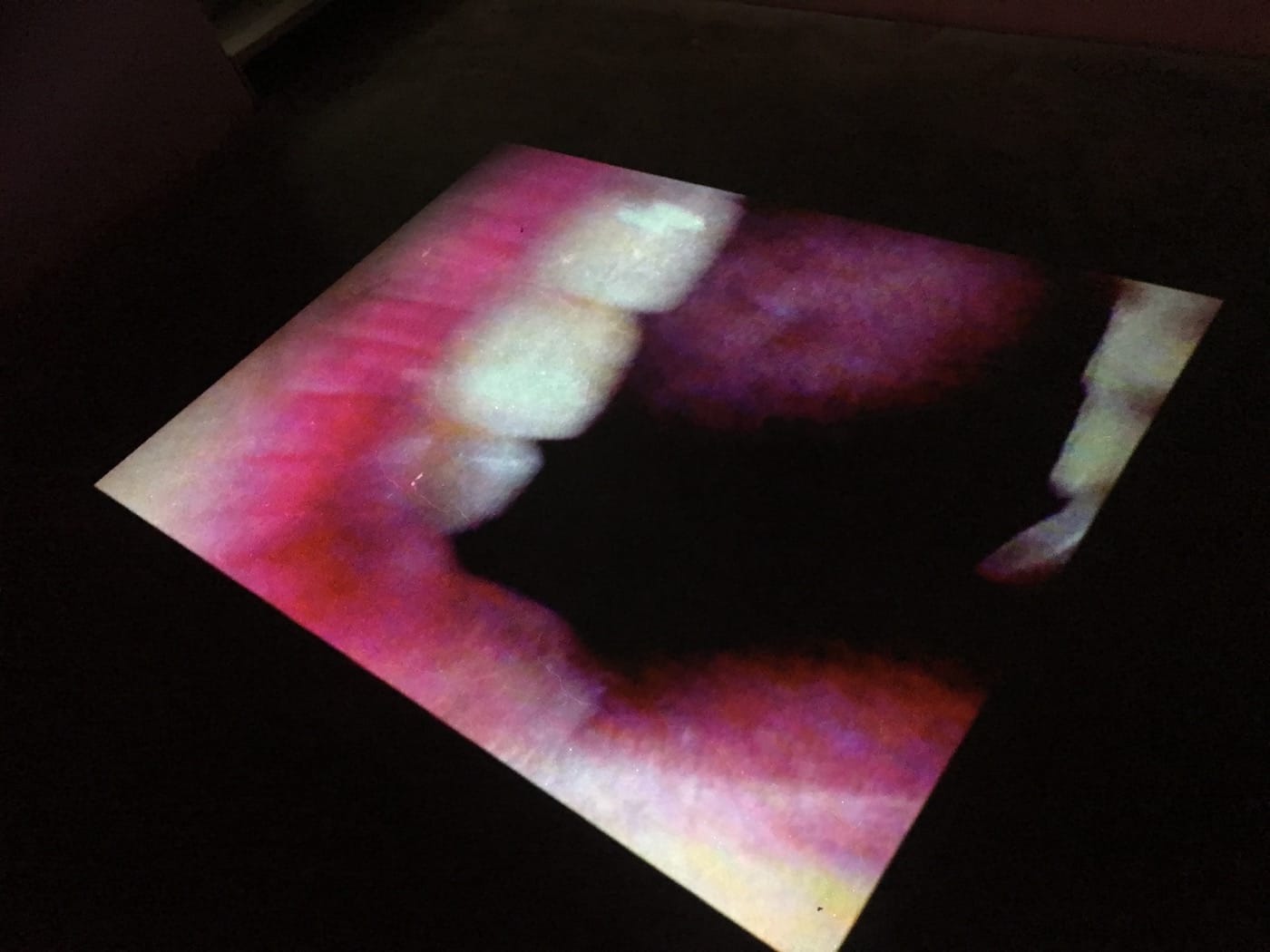

Projected on the floor, the video embodied the title of the show while single-handedly defining its outré ethos. As I wrote in my review for the Brooklyn Rail, the artist’s nude body, resembling “a soft, milky caryatid awash in hot Impressionist pinks, yellows, greens and violets,” is encircled by a constantly moving camera that seemingly “dives deep into her mouth and pops out of her anus, only to whirl back up to her open mouth—giving you sensation of being swallowed and expelled, swallowed and expelled, into infinity.”

It’s a work of art that’s nothing if not fearless, and if you want to see it for yourself, “Mutaflor” is currently tucked into a third-floor corner of Pipilotti Rist: Pixel Forest, the dazzling retrospective at the New Museum curated by Massimiliano Gioni, Margot Norton, and Helga Christoffersen.

In the past decade or two, much has been said, and much of it derogatory, about art as spectacle: that it’s all flash and no substance, digested and forgotten, appealing to abbreviated attention spans and the magnetism of all things bright and shiny. But from the evidence of its previous show, The Keeper (curated by Gioni, Natalie Bell, Christoffersen, and Norton), and in a quieter way, Anri Sala: Answer Me, which was mounted earlier this year (curated by Gioni, Norton, and Bell), the New Museum seems to have taken it upon itself to produce spectacles that are as moving as they are eye-filling. Pipilotti Rist: Pixel Forest is something else again.

By filling the galleries to the brim in The Keeper and emptying them out for Anri Sala, the museum managed to tame its awkward layout, in which elevator bays encroach on the main galleries and artworks feel alternately lost and crowded in the squeezed, double-height space.

With Pixel Forest, the architecture feels as if it were designed for the show rather than the other way around. Rist has all but dissolved the walls and ceilings through the strategic deployment of video screens, black paint, fluttering sheets of sheer fabric (“Administering Eternity,” 2011), and hanging cables studded with LED lights (“Pixelwald,” or “Pixel Forest,” 2016). But the expert use of space is just the setup: Rist has reimagined the idea of video display to such an extent that each floor, including the nooks and crannies, presents a wholly different tour de force of light, sound, and surface.

The show proceeds chronologically, with single-channel videos from the 1980s and early ‘90s encased in head-high, long, narrow pyramidical enclosures projecting menacingly from the facing walls of the corridor behind the second-floor elevators. In order to see each work, you have to stick your head through a hole cut in the pyramid’s bottommost plane. Soundproofing foam covers the enclosure’s interior to keep the audio in and the rest of the world out, creating a uniquely one-to-one experience with the work.

These videos are the only pieces that are cordoned off, so to speak, from adjacent works. While there is remarkably little audio bleed in a show this sprawling and complex, everything else seems to spill into everything else, even on the staircase between the third and fourth floors, where “Selbstlos im Lavabad” (“Selfless in the Bath of Lava,” 1994) — a video loop of the artist crying out from a lake of fire — plays on an iPhone lying on the concrete landing, as if it had dropped from a curator’s pocket. Hanging in a niche a few steps away, there’s “Komm bald weiner” (“Come Again Soon,” 2016), a framed seascape embellished by iridescent pools of digital color . Though done more than a decade apart, the placement connects and energizes the two works, allotting each more presence than it might not have otherwise possessed.

Outside of these tightly compressed byways, the exhibition takes off into a lavish, dizzying, heart-tugging spectacle that’s as much a social construction as a visual one, where the presence of people is built into the conceptual fabric of the large-scale works.

In “Administrating Eternity,” the video projections on the floor-to-ceiling sheer curtains are inseparable from the shadows of visitors wandering through them, just as the movement of bodies through the ever-changing colors of “Pixel Forest” continually transforms the look and feel of the work.

For the installations sited in the corners of the galleries, cushions and carpets are as integral to the piece (and recorded as such in the checklist) as the video projections. As the non-narrative montage streams past your eyes, you’re aware of watching and not watching at the same time: the elusiveness of the swirling imagery sinks into your subliminal perception, sending your thoughts inward, but you can never be unmindful of the others around you, who are comparably transfixed.

In “Fourth Floor to Mildness” (2016), an installation the artist designed specifically for the fourth floor of the New Museum, Rist makes her most audacious move yet by crowding the large gallery with more than a dozen single and double beds covered in blue or green bedspreads. The idea is for visitors to stretch out on the mattresses and watch the videos projected on two large, amoeba-shaped screens hanging from the ceiling.

To lie on a bed in public, with the potential of falling asleep, is an expressly vulnerable act, one that has been exploited in such performance pieces as Chu Yun’s “This is XX” (2006) and “The Maybe” (1995), the collaboration between Tilda Swinton and Cornelia Parker. But Rist is putting the audience, not a performer, in that position, and it should rightly feel odd, if not threatening, to contemplate bedding down in a darkened room full of strangers. The similarity to a disaster relief shelter is unmistakable.

But “Fourth Floor to Mildness” doesn’t seem intended to abrade your inhibitions; after all, you have the choice to recline, sit, or remain standing. Rather, Rist is inviting us to unguardedly immerse ourselves in the sensory overload of video and music. Lying there, with your eyes trained on the images unspooling across the ceiling, you can’t see the people around you, as you did in the show’s other large video installations. But you can sense their presence, and their rustling and whispers become an essential, living strata of the piece (as would, if you were with a loved one on a double bed, that person’s breathing and touch).

That sense of intimacy threads around and through the work, its visuals filled with close-ups of rippling underwater flora and the waterlogged skin of the artist’s face, fingers, breasts, and feet — a haunting beauty that only deepens with choice of the song “Spiracle” by Skin&Soap (the Austrian musician Anja Plaschg) for the soundtrack: an innocent-sounding melody whose lyrics are laced with violence: “When I was a child/I threw with dung as I fought/As a child/I killed all thugs and bored with a bough/In their spiracle.”

The acrid sweetness of “Spiracle” encapsulates the extravagantly layered resonances of a show in which every shimmer of beauty is undercut by mayhem and decay, where every shower of light is ringed in metaphorical darkness, and every sensation is designed to connect.

Pipilotti Rist: Pixel Forest continues at the New Museum (235 Bowery, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through January 15, 2017.